Episode 8 - Postcards from The Kitchen, “A Tale of Two Tacos”

More than being delicious, food can bring people together, heal the body and soul, and is intertwined with generations of history and tradition. Today, we’re gonna dig into some of this by getting a taste of South Texas. We’ll start at its end point in Brownsville, then visit its gateway in San Antonio. Along the way, we’ll see what a good meal can tell you about a place, but best of all, hear from the folks doing the cooking. You could say this is a tale of two cities, but it’s really a tale of two tacos.

TRANSCRIPT

(As this transcript was obtained via a computerized service, please forgive any typos, spelling and grammatical errors)

________________________________________________________

Evan (00:01):

The people I come from are food obsessed. We've planned entire trips around eating and are known on occasion to discuss dinner plans in the middle of lunch. So, I think George Bernard Shaw was really onto something when he said, "There is no sincerer love than love of food." More than being delicious, food can bring people together, heal the body and soul, and is intertwined with generations of history and tradition. We're going to dig into some of this today by getting a little taste of south Texas. We'll start at its end point in Brownsville, then visit its gateway in San Antonio. Along the way, we'll learn a bit about what a good meal can tell you about a place, but best of all, hear from the folks doing the cooking. You can say this as a tale of two cities, but it's really a tale of two tacos. I'm Evan Stern and this is vanishing postcards,

Adela Vera (01:08):

Born and raised. What can I say? I love Brownsville. This is my hometown. I go out and we go on vacation and I'm longing to come back because this is where home is really-

Evan (01:18):

Before leaving Corpus this morning, I pulled into a full service gas station to have my steering wheel fluid checked.Striking up a conversation, the tall sunburned attendant asked where I was going. I said, "I'm heading down to Brownsville." "You coming back tonight?" He asked. When I told him no, he said, "I'm sorry." Like all people, the good citizens of Brownsville have many wants, needs and dreams. Speak with the folks around here, and most will acknowledge that this border city at the southernmost tip of the central United States has its share of challenges, but pity isn't something I think any of them are after.

Adela Vera (02:03):

Um, and I want to say that in every area of the country, there is that part of, of, of the environment that you live in. Right? There's always poor. There's always-. And yes, compared to the country, and yes statistics show that we're one of the poorer states, or area actually here. And, and yes, definitely. We have to, to progress. I am I'm all for that, but I don't know. I just consider myself good. Rich, I guess I could say that. Not, you know, rich, uh, per se, because I have what I need and yes, uh, um, I'm an educator and yes, I can see in my children, some of my children are- they need some, so many resources, you know. But, at the same time, they're loving. They're they're good children. They're they come from good families. They're in a good place. It's a good place to live.

Evan (02:58):

I'm speaking with Adela Vera in the front room of Vera's Backyard, Bar-B-Que, the takeout counter/restaurant she runs with her husband Mando. It's Friday afternoon, they've just finished service. And she's sitting down preparing containers of onion and cilantro for the coming Saturday onslaught. They're only open three days out of the week from 5:00 AM to 2:30. But given Adela's teaching schedule, you can't call any of what she does part-time.

Adela Vera (03:27):

Monday through Friday, I'm at school basically. And I'm there. I'm usually there until four, five o'clock basically. Saturday and Sunday, this is where I am up to about two or three o'clock in the afternoon. So it's a whole week's worth, worth of work.

Evan (03:43):

How many years have you been doing that routine?

Speaker 2 (03:47):

Uh, well, we've been married, uh, 35, approximately 35 years. So that's how much that's how long I've been

Evan (03:55):

Not one for martyrdom, she's quick to tell me she's taken days off, vacations and traveled a bit. Her husband Mando, though she says, doesn't know the meaning of rest. Just then he enters from the back and plops down in front of a large fan to cool off. Mando is a big guy. He sports, a mustache work boots and his t-shirt and jeans are smudged with ash. He smiles at me with his eyes and gives a welcoming tip of his ball cap, but his tiredness is palpable and I can't help but feel intrusive in speaking with him at this hour.

Evan (04:33):

Again, thank you so much for letting me come in here to talk to you at the end of your day. I mean, I know you have a lot of work left to do. What time did this day start for you?

Mando Vera (04:43):

Uh, around four o'clock in the morning today, I got here at 3:30, so 3:30, 4 o'clock it depends on how back, uh, backed up I am-

Evan (04:49):

I soon learned, this was far from the end of his day and little about this operation is what you might expect. Let's start with the name- "Vera's Backyard Bar-B-Que." They do offer brisket, but that's not the draw and you won't find ribs, sausage, coleslaw, or any of the usual Texas trappings here. No, this place is about barbacoa. Bar

Mando Vera (05:14):

Barbacoa, it's Mexican barbecue. So it's, uh, it's beef head barbecue. That's what it is. So you take the beef head and you cook it. You know, we've done it the old way, the traditional way that we've got a pit, we've got a hole in the ground. That's our pit. You know, we cook with mesquite wood. A lot of the barbacoa places or the Mexican barbecue or not are not using the beef head. You know, they they're using, uh, uh, cheek meat, which they sell by the case -

Evan (05:45):

Beef head barbecue. Actually the term barbacoa is generally agreed to have evolved from an amalgam of the Spanish words for beard and tail, meaning that everything in between gets used and to any vegetarians listing, you might want to close your ears because looking at the menu here, which even includes sesos, brains, that seems to pretty much be the case.

Mando Vera (06:09):

It cooks over 10, 12 hours. Uh, and then you have a choice of, do you want lean? You want cachete which is the lean? You want lengua which is the tongue? You know, the Mexican caviar, which is the eyeballs. You know, that's, that's, that's caviar, there, you know, and that's something that's sold out by eight o'clock, nine o'clock, 8 30, 7:00, you know?

Evan (06:33):

Did he just say eyeballs?

Mando Vera (06:36):

You know, you get people calling a day before, two days before, you know. I got a guy called me, uh, as a matter of fact, the guy called me this morning, he's coming down from McAllen, which is about an hour away. And he wanted two pounds of eyes. That's what he wants.

Evan (06:49):

I like to think of myself as pretty adventurous, but can't say I'm in the mood to give that a try anytime soon. Funnily enough, Mando himself actually admits that he only tried one for the first time, about three years ago. It was also his last. And I'm sure some of you squeamish types out there might be wondering how the hell people started doing this in the first place. Well, barbacoa is a working man's food. It started in Mexico and has a long history here in The Valley where ranch hands and vaqueros were given the leftover scraps that nobody wanted. And when you look at the evolution of cuisines around the world, this is often how some of the best meals have been discovered.

Mando Vera (07:31):

So barbacoa, it comes from Mexico. So, so, um, you know, out in Mexico, in the ranches, you know, it's, it's a different, it's a different world, you know, out there that they, they kill a cow or a calf and the meat has to go, you know? And, uh, after they took everything out, it was a beef head, so what do we do with a beef head? So, you know, the ranchers out there, they dig the hole, they, they, they start a fire and that's how it came to be. You know, they put the beef head in there. So, you've got Mexican barbacoa now.

Evan (08:03):

Cooking a head, right Is a process. To be fair, there are plenty of great chefs out there who have figured out how to do this well, but Mando is special because when he talks about his pit, he isn't describing a smoker or brick oven. He's the only guy in this entire country who's legally allowed to sell barbacoa as it was intended- out of a literal hole in the ground.

Mando Vera (08:30):

Okay. So, so in cooking the head, what we do is we start the fire. We got to get a hole in the ground, which is a pit actually, uh, it's lined with a Firebrick. And, um, we start the fire. The fire goes on for about anywhere from six to eight hours. And, uh, once those, uh, those mesquite woods are burned and they turn into charcoal, then, then, then we put sheet metal there and we put the barbecue in the pit. And once it's in the pit, we cover it with a sheet metal, we seal it with dirt. And, um, it stays there for about another 10, 12 hours, you know? And, and by the, by, by then, it's ready to go.

Evan (09:14):

Mando will tell you that cooking underground gives the meat a pure flavor that allows it to speak for itself,

Mando Vera (09:21):

It's got that mesquite wood. It's got a different mesquite, the original, you know, and we don't add any spices, no salt, not even salt, you know, so we don't have any spices. It's just a barbecue pit, you know, and the mesquite wood, that's what gives it the taste.

Evan (09:33):

He's right. I ordered the cachete, beef cheek, which I'm told is most popular and fashion three tacos with locally made corn tortillas, onions, cilantro, and salsa verde. It tastes simple, rustic and smoky. And I haven't stopped thinking about it since

Mando Vera (09:53):

Us. We're in a different category, you know, I don't brag about it. Uh, but getting something to getting something to a customer that he cannot get that elsewhere. You know, if you can do it at home, why would you want to go to a restaurant and buy it? You know, you want to get something that they cannot get anywhere else, you know, that's, that's, that's it.

Evan (10:13):

He learned how to do this from his father who started selling here on Sundays 65 years ago,

Mando Vera (10:18):

It was back in 1955. And, uh, it's been here since. I'm the second generation. So I've been doing it for about 45 years. You know, I was, I was like 13, 14 years old when I started doing this

Evan (10:31):

The reason it's called "Backyard Bar-b-que Isn't marketing. It's because the pit was built in what had been the Vera family's actual backyard. I didn't realize it when I walked inside, but the building we're standing in, which now houses the shop was the home Mando grew up in.

Mando Vera (10:49):

I was born, I was raised actually here actually here in this building. Part of it was a house and part of it was a business. So, so yeah, so I grew up here, you know, we had like just our bathroom, our little kitchen and, and just one room. And that's where we, we all, uh, all five of us lived my dad, my mom and, and my three brothers, my three brothers. So, so yeah, it was part of, it was, it was, it's a mom pop shop, you know,

Evan (11:17):

Well, in the last few years, this little mom and pop operation has started to get a lot of attention.

Mando Vera (11:24):

Uh, we've been in so many magazines and books and TV shows. And as a matter of fact, we just got the James Beard award, you know, it's an honor for us to do, to come in from, uh, this part of Brownsville, especially, you know, it's a, it's an area where it's always been put down by everybody, you know? And, uh, for me, it's an honor to go and represent my, my, my barrio, you'd say my, my neighborhood, you know, my, my Brownsville, as a matter of fact, representing Texas for that matter, you know-

Evan (11:56):

Mando isn't in this for the headlines, he was doing this ages before anyone outside of Brownsville took notice and tells me he plans on going for as long as he can.

Mando Vera (12:06):

It's been a life long journey, you know. Tiring, rewarding. I love what I do. Uh, we've had a lot of hard times, uh, uh, thank God. You know, we we're doing, you know, we all, we owe it all to the man upstairs, you know, uh, if it weren't for him, nothing, nothing would have been possible. But, uh, well, I guess I want to keep on going until I can keep kicking, you know? So, so I'm 59. I still got another, I don't know, another 10, 15 years to go.

Evan (12:39):

I don't want to monopolize any more of this man's time, but ask if I can step out back to see the pit. He politely tells me he has a lot of work to do, but if I'm free to go ahead and swing on by anytime between seven and eight. So about five hours later after nap and light dinner, I come back... How's it going?

Mando Vera (12:57):

Man, I'm so damned tired.

Evan (13:01):

So have you, have you been home since the last time I saw you? Have you been home since the last time I saw you?

Mando Vera (13:07):

No, I've been here since three 30 in the morning.

Evan (13:22):

Nevertheless, he greets me with a smile and leads me past a barking neighborhood stray to the shed out back. He opens the door and I'm hit by a wall of heat and the smell of mesquite smoke. In front of us is the pit, a bricked up hole that looks to be about four feet deep with roaring orange flames shooting out of it. It's neat to look at, but it's about 90 degrees outside and humid. And within seconds, I'm completely drenched with sweat, but Mando doesn't judge. I don't think this is something anyone could ever truly get used to even after some 45 years. And in regard to time, I ask if he sees any of his kids taken over.

Speaker 4 (14:04):

No, I doubt it. Um, my, uh, my oldest son is a band director, my, uh, daughter, she's got a graduate degree in Mexican American studies and she does that. Uh, my younger daughter she's, she's doing good. She she's working for a good company and she's doing good, so I don't see them. So you never know. Right. But for now, I don't think so.

Evan (14:30):

So unless some keen apprentice with masochistic tendencies shows up, this saga ends with Mando and traditional barbacoa becomes even harder to find. I get it. Given the heat hours and everything associated with this work, I stand in awe that this fire has been burning for 65 years. Right now, I'm just grateful to revisit it and yearn for an excuse to make the long drive back. And next time someone says, "I'm sorry," when they hear I'm driving to Brownsville, I'll know to say, "You should feel sorry that you're not."

Evan (16:12):

So as I've drilled into your head repeatedly by now, you don't find barbacoa on every street corner. But actually finding good old school Tex Mex is starting to become a challenge as well. Property taxes have forced out family run mainstays like Austin El Gallo, enchiladas with chili con carne isn't exactly health conscious or trendy. And some like the great chef, Diana Kennedy, have railed against this food for decades. But mercifully San Antonio's Mi Tierra is still going strong. Opened in 1941 as a three table cafe on downtown's market square, three generations later it now runs 24 hours and sprawls over 59,000 square feet. Breakfast here is a treat for all five senses, mariachis stroll amongst tables of backslapping politicos, colored lights, and Papel Picado dangle from the ceilings. And if you step in the back room, you'll see a gigantic wall covered floor to ceiling with what's known as the American Dream Mural. Painted with a vibrant cheerfulness, it showcases local business leaders alongside historical figures like Pancho Villa and cultural icons like Selena, Carlos Santana, Flaco Jimenez, and Vicki Carr. Also included in this cavalcade of Latino excellence is a radiant, curly haired, Ellen Riojas Clark.

Ellen Riojas Clark (17:44):

I was born in San Antonio, Texas, and I'm going to die in San Antonio, Texas,

Evan (17:50):

A professor of bilingual studies at the University of Texas San Antonio, Miss Riojas Clark has traveled all over Mexico, written a book focused entirely on tamales recently completed an exhaustive study of pan dulce and is fascinated by what food can tell us about region.

Ellen Riojas Clark (18:08):

So again, geographics, geographics plays a part in, um, how food develops into another form. And, um, and food like culture is not stagnant. It's always changing

Evan (18:27):

Concerning this, I've met no one who's studied San Antonio's food history with greater scholarship. And she's quick to defend Tex Mex against those who dismiss it as quote on quote "inauthentic."

Speaker 5 (18:39):

Tex Mex is Mexican food. That's the basis for it. So if you deconstruct not very far, it is Mexican food. Enchiladas are Mexican and they're red enchiladas, made with the red enchilada sauce sauce. The only difference in Texas with those is that they put yellow cheese on them. That's that's the only difference. So to me, that's still Mexican food. So, um, you're you're right. I think that that Diane Kennedy, you know, put her nose up in the air about Tex Mex food. I, I don't, I don't disqualify any food because I think it's authentic to that region to that time, et cetera. And it's a good food. I think Tex Mex is good. Puffy tacos are good. Excellent.

Evan (19:36):

Funny she should mention, the puffy taco played a role in my decision to come here. It's one of those signature San Antonio dishes you hear about. So much so, it's the mascot for their local minor league team. But even though I grew up only 80 miles from here, I've never tried one. And the reason Ellen gives for why they're hard to find beyond the 210 area code is pretty simple -

Ellen Riojas Clark (20:00):

Because they're hard to make. I mean, you know, to make it in fast food restaurant is not easy and it takes skill to be able to do that. Like I said, you know, you have to know exactly how, how thin to, to press that masa. Otherwise it just doesn't work. And most of them are made handmade. So, so I don't think that's why it's traveled, but yes, it, I, in my book, it was the original one made was in San Antonio.

Evan (20:30):

Ray's Drive Inn claims to have birthed the puffy taco sometime back in the sixties. But so do a few others. And Ellen says its origin story is challenging to pin down, but she does tell me that Diana Barrios Trevino makes one of the best. And I meet her the following afternoon at her restaurant, Hacienda Los Barrios to try one.

Diana Barrios Trevino (20:51):

My gosh, a puffy taco is not something that my family developed or created. There's a lot of people that argue that their mother, their grandmother, their father, their uncle, you know, I don't even argue with that, uh, who created the puffy taco, but the puffy taco is something that I like to say we perfected. So you take some fresh corn masa, okay. That has been worked with, you know, water and seasoning. You get it to this perfect consistency where it doesn't stick to your hands and you put it through a tortilla press. You can take that corn tortilla or that raw corn tortilla and put it on a comal or a hot griddle and you can cook a handmade corn tortilla, Or you can take that raw corn tortilla and drop it into the hot oil and watch it puff up. And then you play around with it and make an indention and you pull it out and you stuff it with, I mean, you can stuff it with just about anything, whatever you want. We, we, our most popular puffy tacos are the picadillo, which is a ground beef or the shredded chicken in a, in a tomatoey sauce. Or we also have the bean and cheese uh, puffy tacos and the guacamole puffy tacos. Those are really popular. And then they come with lettuce and tomato on top of that-

Evan (22:13):

Like many things in life. She learned how to make this humble creation from her mother. And they've taken her far in this world.

Diana Barrios Trevino (22:20):

She, I don't think she ever expected us to get and to do everything that we have gotten to do with that puffy taco. From being on the food network with Bobby Flay on a Throwdown with Bobby Flay, to going to the lawn of the White House for the congressional picnic in 2010 and cooking puffy tacos, it's just opened so many doors. Um, it's been a wonderful, wonderful expression of love that we get to go and share with the rest of the world.

Evan (22:52):

I tried the Picadillo and can verify that this heavenly, delicate, slightly crispy flavor bomb of a taco is indeed an expression of love. And love is something that Diana radiates as I watch her checking in on both her customers and staff during today's lunch shift. Hacienda Los Barrios is a grand, modern space. And it's just one of four restaurants now owned and operated by Diana and her brother. But she'll tell you the seeds of all this can be traced to a leap of faith her mother took as a young widow over 40 years ago.

Diana Barrios Trevino (23:27):

So it wasn't, uh, it wasn't a dream of hers to open up Los Barrios. It was her last hope. So she invested $3,000 and they rented an old boat garage, no parking lot. There was just parking on the street. Uh, no matching tables, no matching chairs. Very, very humble beginnings because she doesn't, she, a lot of people say, oh, she used her last $3,000. No, that's not the case. She only chose. She only wanted to spend, she didn't want to lose any more money. So she only spent the $3,000. That was all she invested. That was her initial investment. And so three weeks into the project, it was standing room only. But like my brother Louie says when the food is good, there's forgiveness in everything.

Evan (24:14):

Forgiveness is another important word in this family.

Diana Barrios Trevino (24:17):

So our dad died September 1st, 1975. From that day forward until April the 24th, 2008. She prepared us for life without her, because she saw how we reacted after our dad died. I had just turned 12. Louie had just turned 15 and Theresa was 16 about to turn 17. We were very sheltered. We were very loved. We were very innocent in so many ways. And we had to grow up overnight and it was, and my father died in a car accident. My mother was murdered by her neighbor. They couldn't, the way we handled it. Everything was very different with the death of my dad, my brother just, you know, he and my father were best friends. And so it wasn't good. There was a lot of unforgiveness with his death. The death of my mother- She spent the rest all that time, you know, between my father's death and her death preparing us. And what she fed us, not only her cooking, but what she fed us was a lot of spirituality.

Diana (25:26):

And, um, you know, the day she died dying, the way she did, um, people were very, they couldn't understand how we could be so forgiving. We had all three of us, my sister and my brother-in-law. We all had children. We had children and, and they were young and my mother would have been so disappointed if we had reacted, um, in an unforgiving manner. She would have been so disappointed in us because that's, that would be what we would be teaching her grandchildren. And that was the furthest thing she'd want. My mother was about forgiveness, never holding a grudge and, and being kind and loving. And, you know, and knowing that you make those choices, those are choices that we can make. And it doesn't cost anything to make them. You just gotta make up your mind. And you know, doesn't mean that, you know, we didn't think this kid who murdered our mom shouldn't pay the price

Diana Barrios Trevino (26:34):

He's in jail for the rest of his life. He'll never come out ever. But forgiving. Yes, we have to be forgiving because that's what were taught. And that's how we honored our Mom.

Evan (26:48):

And when did you go back to work?

Diana Barrios Trevino (26:50):

After my mother died, um, let's see. She, she died on Thursday, Friday, Saturday, and Sunday, Monday, Tuesday. I think I went back to work the next Wednesday. And my brother had told me, "You need to stay home a couple of weeks. I mean, we've had, we've gone through a whole lot." I said, "Louie, I can't, she's in my ear going, 'I know you miss me. You got to get back to work!'" And he called me and he said, "How are you? Are you okay?" I said, "I'm, I'm real good. But our customers are not, they they're, they're so heartbroken. And they're so sad. It's like we would minister to them and let them know, you know what? We're okay. Mom's okay. We're going to focus on how she lived her life, not on the last 10 seconds of her life. And it was very therapeutic. It was very therapeutic to get back to work and like it or not, sad as I was, I had to get back to work because she was in my ear going, "Who's minding the store, you know, get back to work. We've got to take care of our customers. We gotta take care of our employees. We gotta make sure, you know, everything is spot on!"

Evan (28:00):

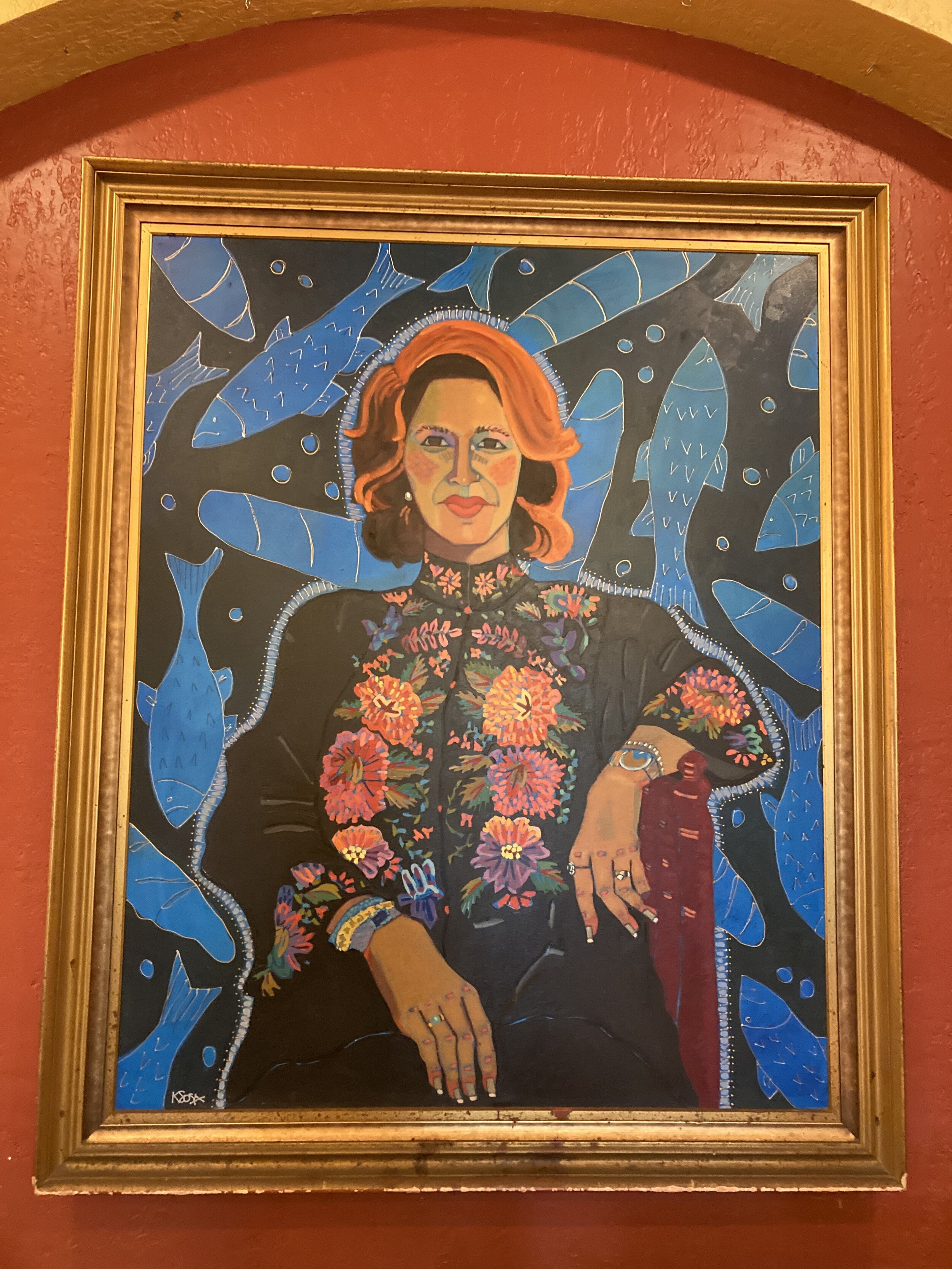

Enter any one of their establishments, and you'll see a painting of the elder Miss Barrios seated, keeping a regal eye over her beloved Patrons. Her spirit lives on through her children, the food they serve a charity and restaurant named in her honor.

Diana Barrios Trevino (28:18):

Now we have another restaurant that we opened after my mother passed away and it begged to be named in her honor done in her memory. And so the restaurant is named Viola's Ventanas. My mother was Viola and Viola Ventanas, because my mother loved windows. And my brother says, if you could look into the, if you could look through the window into my mother's soul, you would see her showing her love by cooking for people. That's what she did. She loved doing that.

Evan (28:48):

I began this episode by quoting George Bernard Shaw, but I'm now reminded of Cesar Chavez, who once said, the people who give you their food, give you their heart. That's what Diana and Mando do. Different cities, different tacos, different processes, different histories, but in the end, it all comes back to love.